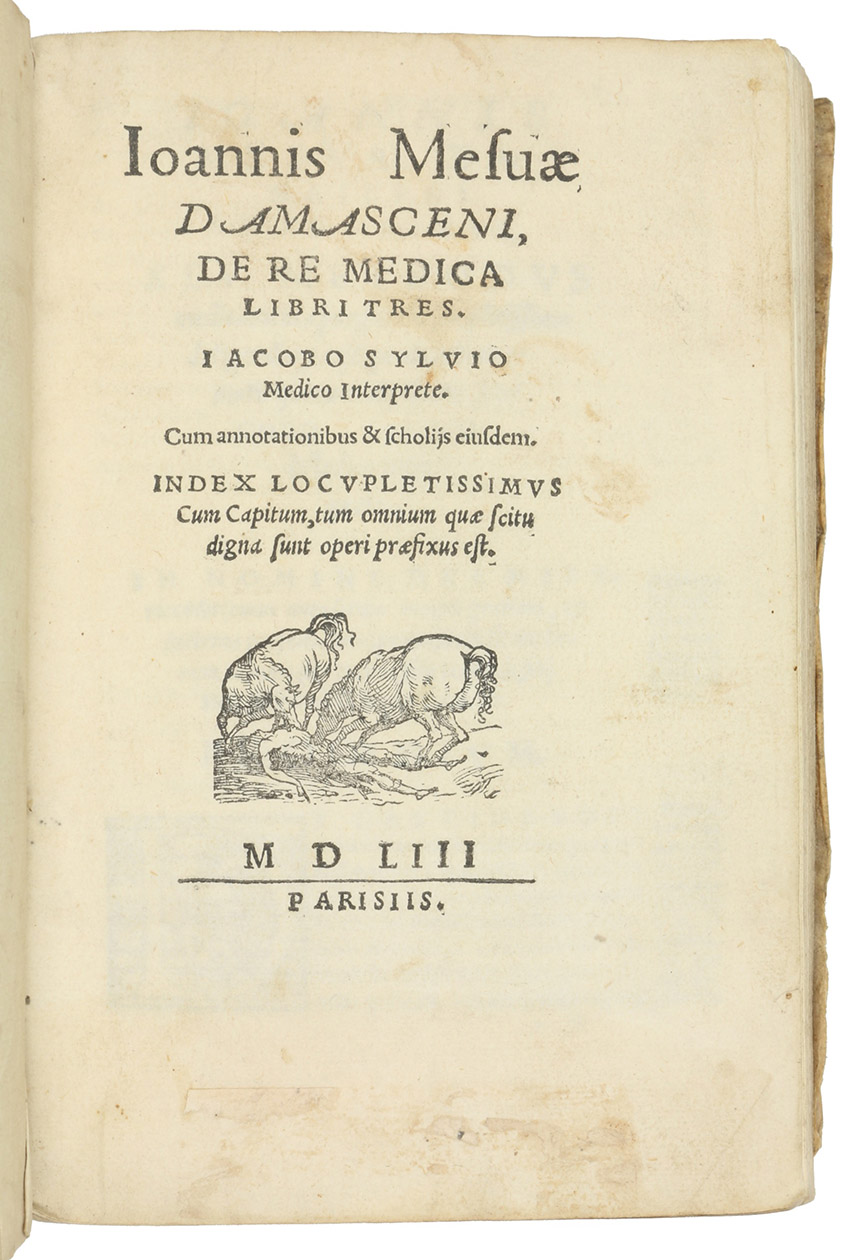

MASAWAIH AL-MARDINI (MESUE the younger).

De re medica libri tres. Jacobo Sylvio medico interprete. Cum annotationibus & scholiis eiusdem. Index locupletissimus cum capitum, tum omnium quae scitu digna sunt operi praefixus est.

"Paris" [= Venice], [Girolamo Scotto], 1553. 8vo. With Scottos woodcut device on the title-page (showing what are probably two of the wild mares of King Abderus being devoured by the mares of King Diomedes of Thrace devouring either Abderos or Diomedes himself) and about 22 woodcut decorated (nearly all pictorial) initials (7 series) plus a few repeats. Contemporary vellum, traces of ties. 248, [4] ll.

€ 7,500

Rare Venetian edition with a false Paris imprint, of Mesues three seminal pharmacological works, including his great pharmacological handbook, the principal model for the European pharmacopoeias, translated into Latin by Jacques Dubois/Jacobus Sylvius (1478-1555), who taught anatomy at Paris (his students including Vesalius and Gesner). Dubois first published it in a Paris folio edition in 1542. As far as we know, the present edition has not previously been recognised as a false imprint, but Girolamo Scotto in Venice used the woodcut device on the title-page in 1543 (Bernstein, Music printing, p. 88 & fig. 3.16: much more "artistic" than most publishers devices, so perhaps made to illustrate an unidentified book) and the woodcut pictorial initial on r8r also appears in Lippomano, Espositioni volgare, Venice, Girolamo Scotto, 1554 (A4r), where some of the types match as well. Moreover, the 2 initials in the largest series (A on l2v and H on e2v) show respectively: another Scotto device (anchor with "S O S" and the motto "in tenebris fulget": see Scottos 1554 Lippomano, 1555 Aquinas and his heirs 1585 Monte, Madrigali) and the coat of arms of the Medici Grand Dukes of Tuscany (dexter) impaled with a tree atop six mounts (sinister).

De Vos calls Mesues present works "a conduit for the Arabic contributions to that epistemology and its subsequent development and impact", describing them as "the most dominant source of pharmaceutical writings" and "by far the most influential in the subsequent development of European pharmacy", with Duboiss new Latin translation "of particular note" (pp. 668, 670, 673). Though these Mesue works had been printed already in 1471, Duboiss translation became the standard, De Vos counting 17 editions in less than a century. The preliminaries include the title-page, Duboiss 7-page dedicatory epistle addressed to Etienne de Poncher (1446-1529), Bishop of Bayonne and chancellor of the University of Paris, and an 8-page contents covering all three works. The three Mesue works follow: "Methodus medicamenta purgantia simplicissima deligendi & castigandi, theorematis quatuor absolutus" [= Canones universales?], ll. 1r-33v (13 chapters); "De singulis medicamentis purgantibus deligendis & castigandis" [= De simplicibus], ll. 34r-82v (30 chapters); and "De antidotis" [= Antidotarium or Grabadin], ll. 82v-239r (12 sections); followed by definitions of the technical words, ll. 239v-248r, and a 9-page table of contents for all three works. Duboiss version of the first work differs considerably from earlier editions, where it bore the title Canones universales. It describes general techniques in the preparation of medicines and was originally closely associated with the "simples" in the following work, but it was given a much broader application. The De simplicibus, originally gave information on 49 "simples" (mostly purgatives) here expanded to 53. Although it includes many known since classical antiquity, more than a fourth are additions made by the mediaeval Arabic physicians. The bulk of the book is devoted to the Antidotarium (also called Garbadin, after the Arabic for "dispensary"). It is by far the most detailed and extensive mediaeval book of pharmacological recipes, far surpassing the 12th-century Antidotarium Nicolai, which had been the standard work in Europe. Not only does it include 432 recipes for compound medications (compared with Nicolais 85), it arranges them by the kind of medicine, rather than alphabetically, and unlike Nicolai it gives detailed instructions for their preparation. It largely superseded Nicolai in Europe in the late 1300s and early 1400s. Although Mesue and his present works have fallen into undeserved obscurity in the general public, they went through more editions than Ibn Sina (Avicenna), Galen or Discorides.

If the attribution to "Joannis Mesuae Damasceni" is correct, the author must be Yahya (= Yuhanna) ibn Masawaih al-Mardini (ca. 925-1015), known in the West as Mesue the younger. He is said to have been a Syrian (Jacobite/Nestorian) Christian physician from Mardin in upper Mesopotamia (now on the Turkish-Syrian border, who worked in Damascas, may have headed the Baghdad hospital, served as personal physician to caliphs in Cairo and wrote in Arabic. His present principal works are now known, however, from Latin translations, the earliest from 1281, and De Vos even suggests they may have been compiled in Bologna after 1260, adapting several unidentified Arabic medical works of the 10th and 11th centuries to 13th-century European needs. She notes that Dubois published a "new" Latin translation in 1542 and emphasises its importance, but she does not discuss his sources (he was well-versed in Greek and Hebrew, but apparently not in Arabic). In any case, the writings attributed to Mesue the younger clearly derive from the mediaeval Islamic world and contain many innovations that provided the basis for the theory and practice of pharmacology for centuries and perfectly met the demands of the developing medical marketplace of mediaeval Europe. The early Paris folio editions of Duboiss translation would have been out of reach of most students and country or small town physicians or apothecaries, so Lyon printers introduced 8vo editions in 1548. The present 8vo edition appears to be the first outside Lyon and Scotto may have thought a false Paris imprint would make it seem more authentic than the Lyon competitors.

With faint brown stains, some marginal worming near the end of the text and the corner of Aa3 lost (not affecting the text). Durling 3145; ICCU, NAPE 006561 (8 copies); USTC 151259 (2 copies); WorldCat (9 copies in 7 entries); cf. Brockelmann, GAL I, 232; Hirsch I, 171f; not in Adams; BM STC French; EDIT 16; Wellcome; for Mesue and the present works: Paula De Vos, "The Prince of Medicine: Yuhanna ibn Masawayh and the foundations of the Western pharmaceutical tradition", in: Isis, 104 (2013), pp. 667-712; Prioreschi, History of medicine, IV (Byzantine and Islamic), pp. 290-291.

Related Subjects: